This is a summary write-up describing the culminating project for my Master of Architecture at the University of Minnesota.

Background

Daylighting has been strongly associated with architecture throughout the

world since prehistoric times. Allowing daylight to form architecture and allowing

architecture to be formed by daylight can be best accomplished by understanding

the effects and behaviors of the sun from an objective understanding in addition

to a more subjective perception. This project incorporates both the objective and

subjective understandings of the sun’s behavior to demonstrate the architectural

potential of daylight using representations of collected information in addition

to generated proposals for interventions at locations throughout the world. The

project is framed under the concept of heliotropism, which is the phenomenon

by which animals and plants turn towards the sun. This project studies how architecture can allow humans to turn towards the sun and better understand their

positioning in the world and the universe.

he·li·ot·ro·pism

the directional growth of a plant in response to sunlight

the tendency of an animal to move toward light1

Understanding the Dynamic Qualities of the Sun

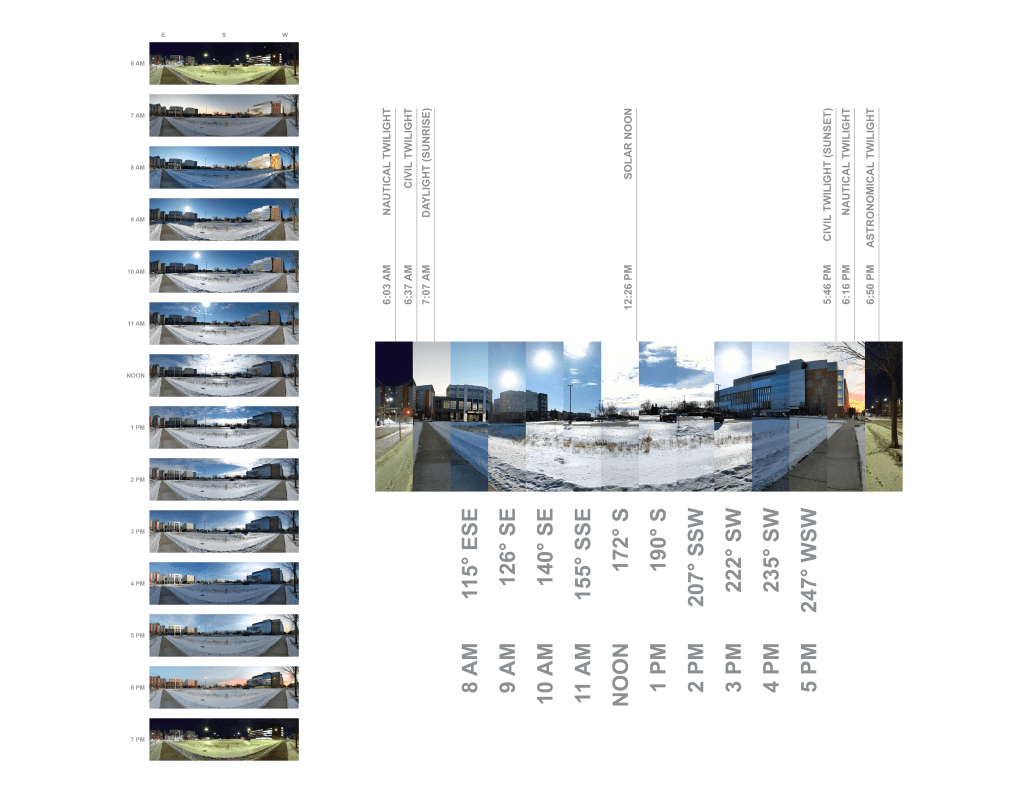

Using rigorous processes, this project emphasizes the dynamic qualities of the

sun’s interaction with Earth and its perceived movement from Earth throughout

the day and year. Some of these processes—such as the change in altitude of the

sun’s path throughout the year—are very gradual, and for those processes, being

able to track and represent them at a large time scale becomes advantageous.

Some other processes—such as the transition between day and night in the

twilight hours—happen on a smaller time scale, but capturing multiple moments

within the change is important due to the large change in daylight and color

between day and night. Furthermore, there are instantaneous moments—such as

solar noon of the solstices or equinoxes—which in this project are architecturally

communicated through representations of current conditions and in imagined

spaces.

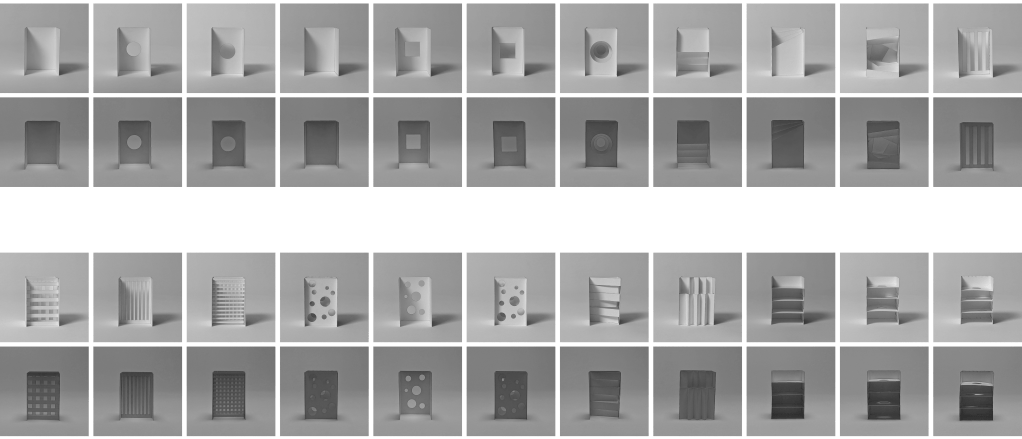

photographed with diffused lighting from the side and from directly overhead.

Representing Subjective Experiences of the Sun

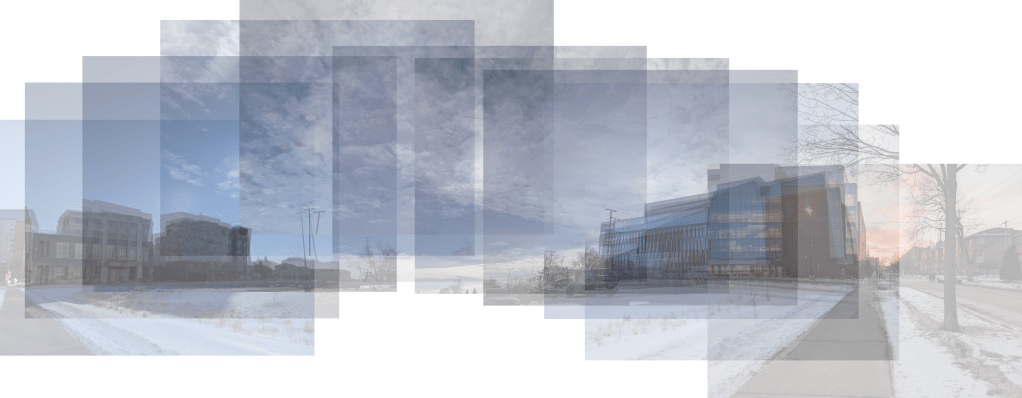

A major theme in this project is the exploration of representations of the sun

and its effects, in order to find a deeper understanding of how daylight interacts

in inhabited space and how it is perceived at the human level. These explorations

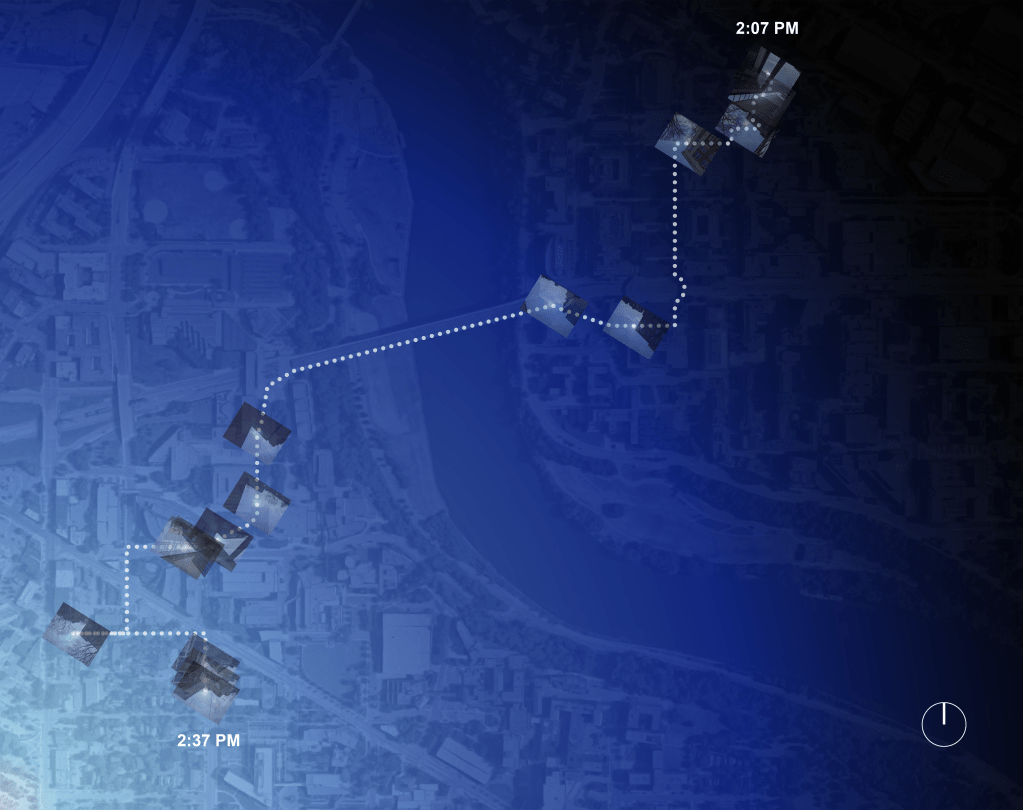

include collection of data at the human scale in addition to experimentation with representations that tell the story of that process. One example is a study where

I took photographs of the sun in Minneapolis for thirty minutes while walking

towards it. The simple rules dictating this study were as follows:

- Walk towards the sun

- If something obstructs my view of the sun, keep walking towards the sun until it reappears

- When it reappears, take a photo of the sun such that it is centered in the frame

- Repeat the above steps

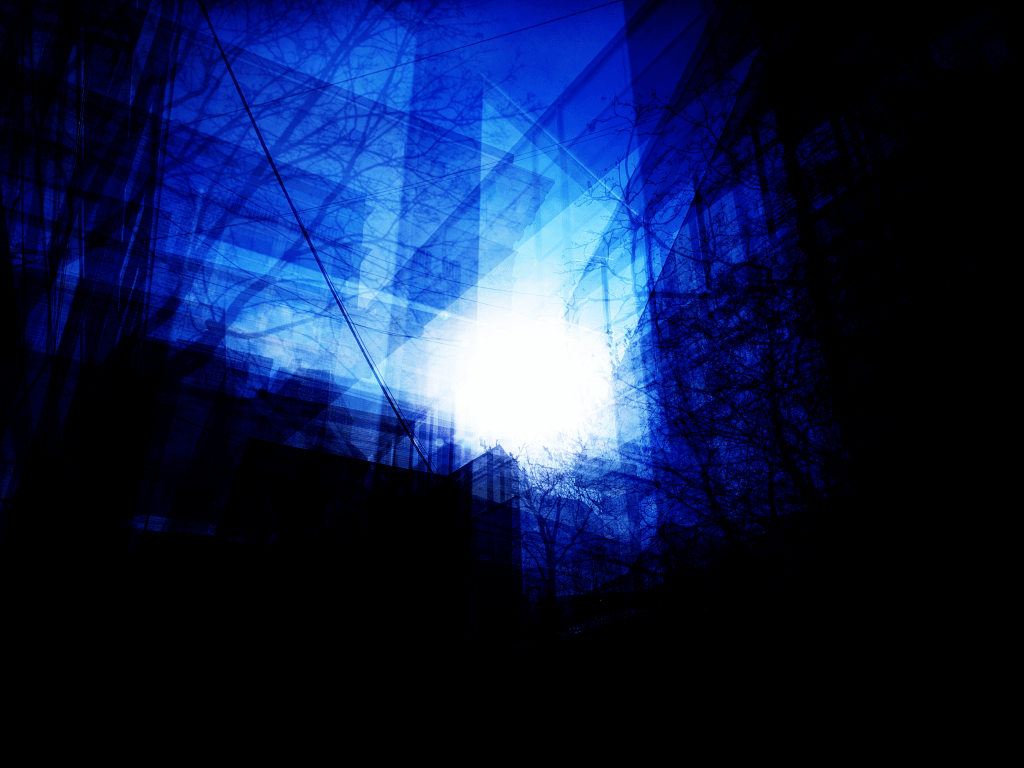

After collecting the photos from this study, the photos were overlaid and

Photoshop blending modes were experimented with to produce the image

on the left which demonstrates the spatial qualities of daylight in the urban

environment of Minneapolis, and the perception of being drawn towards the

source of the daylight.

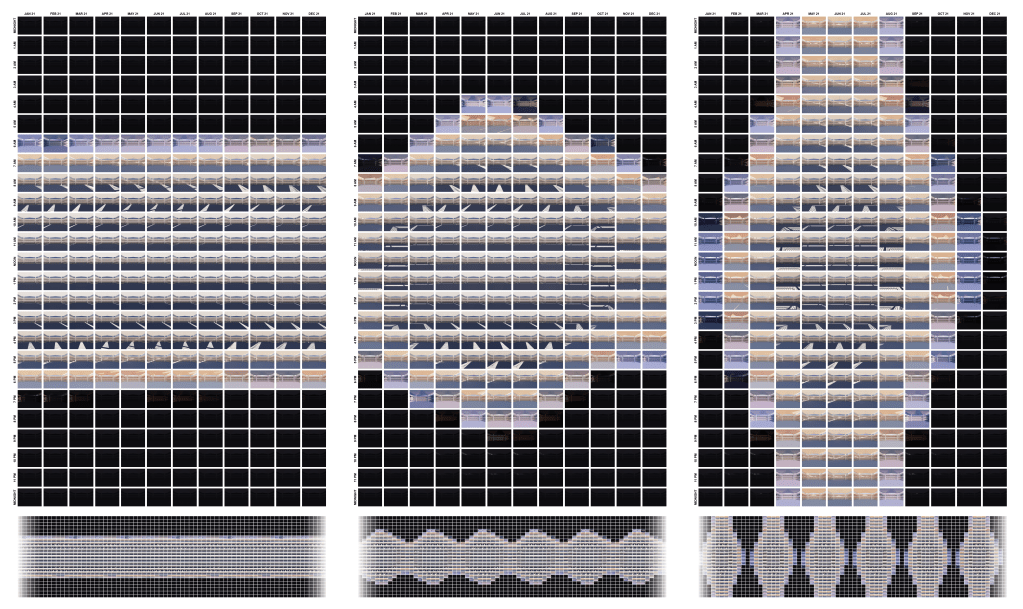

Other studies tracked the movement of the sun from a single location over a

long period of time. The movement of the sun in these studies are represented by

a collage of overlaid images which were taking by pointing the camera towards

the sun or its perceived direction when it was being obstructed. In all of the

studies described, the first-hand experience of being in the environment and

collecting the photographic data became part of the learning process of the effects of daylight. Daylight can be understood in the abstract through quantitative and technical measurements, but it must also be understood through

perception, since the perceived movement and effects of the sun from Earth are

key to fully understanding its architectural value.

The representations made can be generative for architecture by informing

how daylighting is received by built and unbuilt environments. They have the

ability to communicate experiences that are not just instantaneous but also

dynamic.

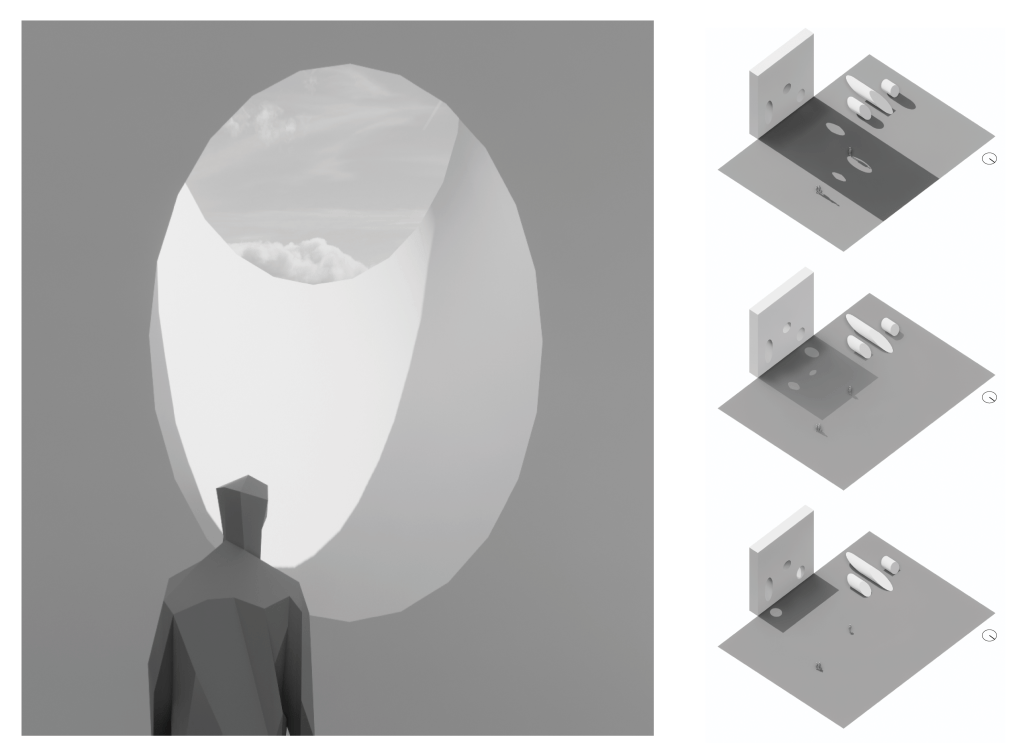

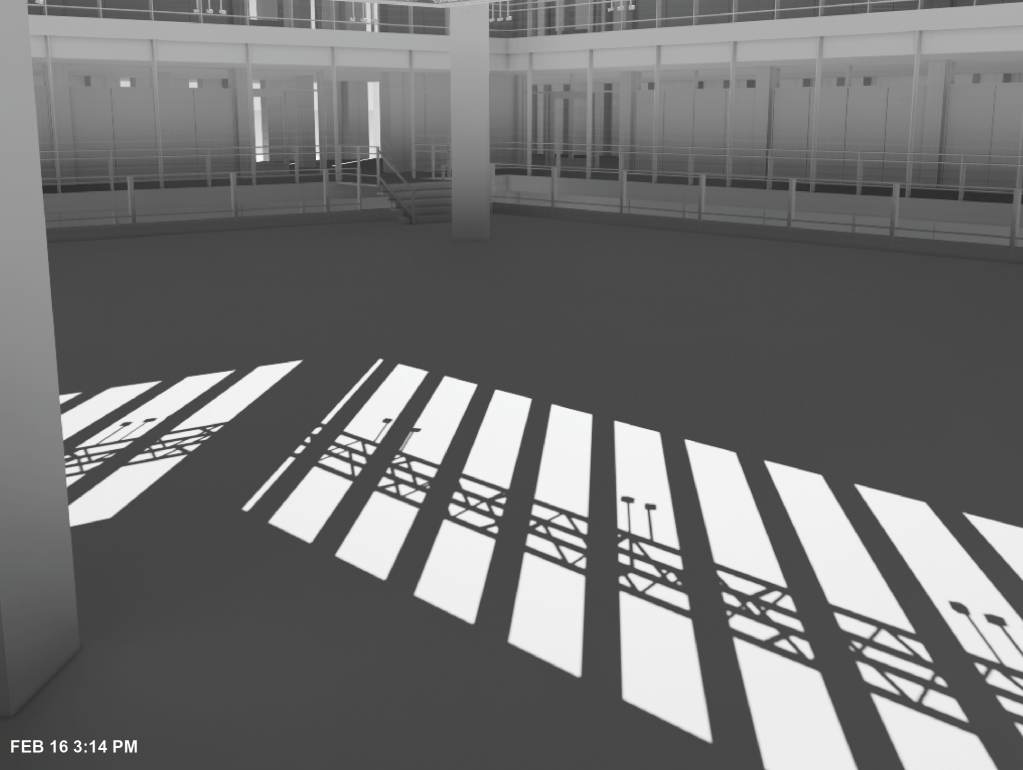

Combining Simulation With Real-World Studies

Architectural designers make use of both simulated realities in addition to

real-world data and documentation when developing an architectural proposal.

These simulated realities can include renderings, digital models, physical models,

and energy models. Real-world data can include site statistics, site climate

data and photography. With respect to daylighting considerations, there is an

important need to be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of simulated

and real-world studies. Simulation has the advantage of being able to give

control over many variables, such as weather conditions, presence of people,

artificial lighting, and location of furniture and people, which can be useful

when assessing the change in other variables. Furthermore, simulation has the

advantage of projecting conditions of proposed possibilities which can be useful

in testing many options rapidly and learning from them. However, all simulations are selective in the variables which are accounted for and neglected, and the

neglect of these variables can be mitigated by combining the simulations with

real-world data. When combined, these two categories of study serve to produce

an ideal understanding of daylighting.

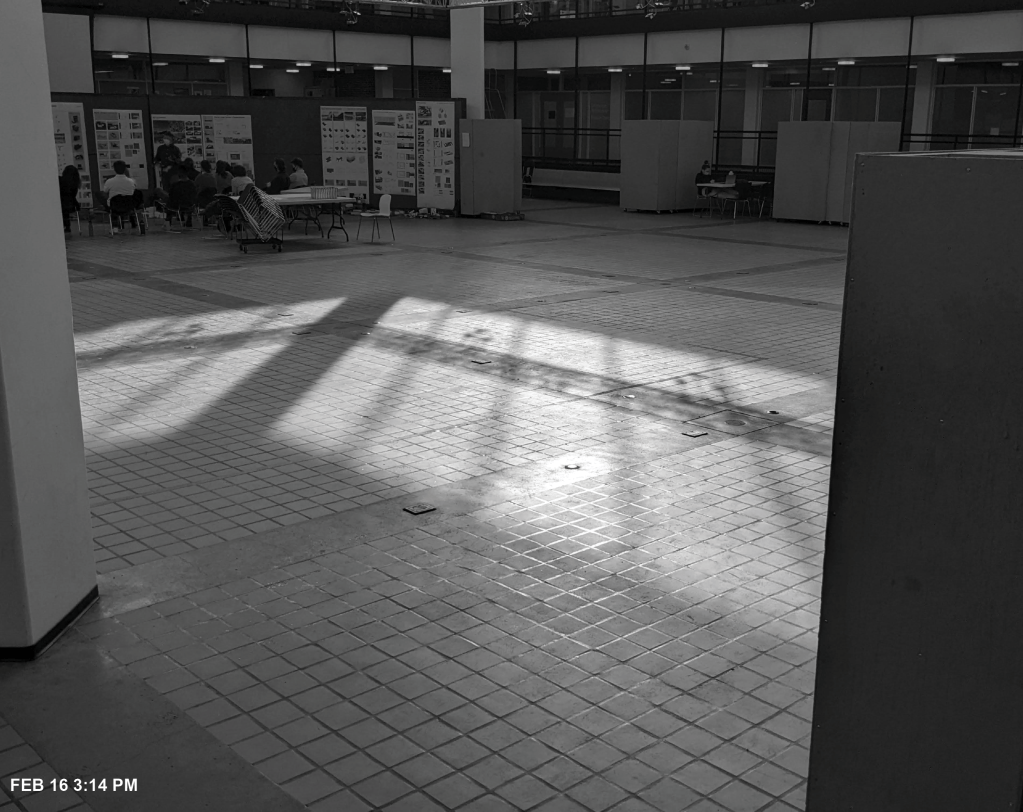

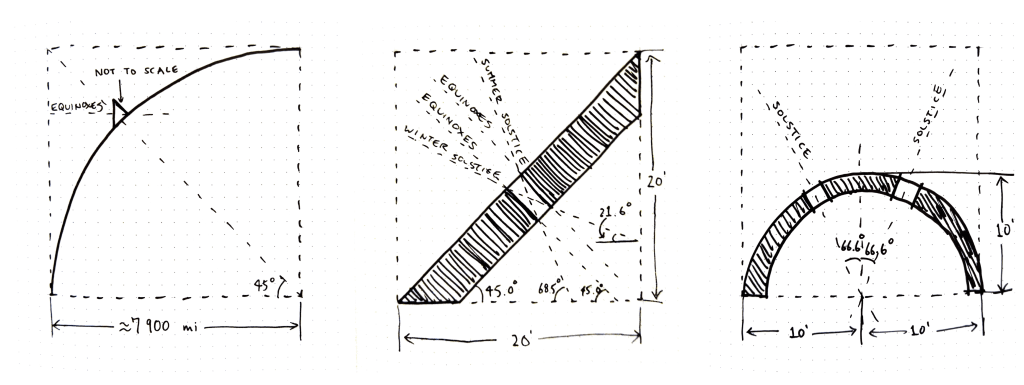

Technical and Experiential Qualities of Daylight in Dialogue

Today, in solar-inspired architectural design, understanding the technical

aspects of daylighting, such as the sun’s altitude, azimuth, length of day, and

daylight availability often play a large role in the development of architectural

form and placement of features such as photovoltaic panels, but these technical

understandings are not always made salient at the human experiential level. This

can be done with simple interventions that are nonetheless carefully determined.

For example, the folly shown on page 13, designed to be placed in a vacant

property near the corner of Erie and Fulton Streets in Minneapolis, consists of

three voids in a large wall. These three voids were subtracted using the same

cylindrical form, but the pitch of the cylinder was aligned to the altitudes of the

sun at solar noon on the equinoxes and each of the solstices. The mathematics

involved in the design are precise, but the sheer scale of the wall also allows for

a rich experience at the human scale even when there is no direct daylight, as the

voids draw one’s view upward.

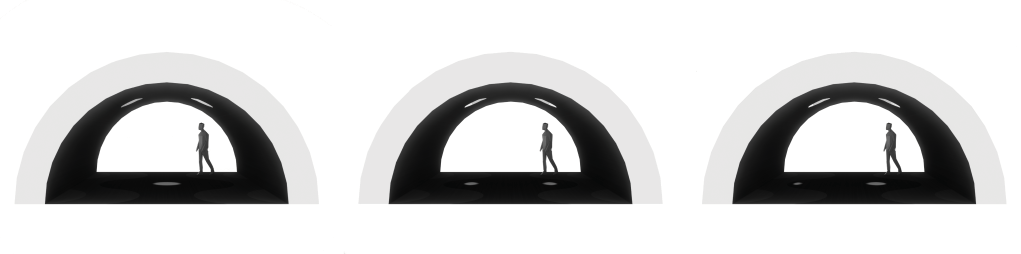

Celebrating Location

People at different latitudes experience the sun differently, and this theme of

varied subjective experiences depending on location on Earth is a major theme

in this project’s explorations. One series of studies explored how a folly would

respond differently to local daylighting conditions when its location was simply

defined by latitude instead of a specific location. Moments such as the equinoxes

and the solstices are highlighted in the latitudes of the equator, 20° N, and 45°

N. However, for the folly at the latitude of 70°N, the unique Arctic condition of

having no daylight in midwinter and 24 hours of daylight in midsummer became

the conceptual driver. Unlike the follies at the other locations, which carefully

employed geometric calculations to project light and shadow, the Arctic folly’s

largest feature is a vertical mirror measuring 20 feet by 20 feet which faces due

south. This mirror highlights the regionally unique conditions of twilight at noon

in winter, and the midnight sun in the northern direction in the summer.

Conclusion

Daylight is essential to architecture and should always be considered at

technical and experiential levels. Technical and experiential knowledge can

inform experimentation which can ultimately lead to architecture which acknowledges and celebrates moments, transition, location, and atmosphere. Because daylight is a free resource, and is accessible throughout the entire world, it has

an immense potential to form and be formed by architecture. My hope is that the series of experiments and designs which I have engaged in can serve as an introduction to this potential.

Citations

- Oxford English Dictionary.

Selected Bibliography

Elkadi, Hisham, and Sura Al-Maiyah. Daylight, Design, and Place-Making. London,

UK: Routledge, 2020.

Guzowski, Mary. The Art of Architectural Daylighting. London, UK: Laurence King

Publishing, 2018.

Magli, Giulio. Archaeoastronomy: Introduction to the Science of Stars and

Stones. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020.

Phillips, Derek. Daylighting: Natural Light in Architecture. Burlington, MA:

Architectural Press, 2004.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Gayla Lindt, Jill Gelle, and Grace Kelly for your feedback and guidance throughout this semester.