The original version of this essay was a research paper produced for an architectural history course. It explores Japanese architectural aesthetics by studying Todaiji Temple in light of the Japanese novelist Junichiro Tanizaki’s essay In Praise of Shadows.

Introduction

Japanese aesthetics and architecture have been influenced by a long history of cultural influences, some inherited from other cultures and adapted, and some native. There have been various attempts to identify the distinctive features of Japanese aesthetics, with Junichiro Tanizaki’s essay In Praise of Shadows being one of these sources. Tanizaki’s essay has been influential in understanding the Japanese aesthetic, particularly as it pertains to architecture. To give a concrete example of how Tanizaki’s argument applies to Japanese architecture, Todaiji Temple will be used as a case study due to its historic significance in terms of politics, society, culture, and technology. This paper will introduce the design of Todaiji, explore key points from Tanizaki’s essay, and then re-examine Todaiji in light of Tanizaki.

Layout

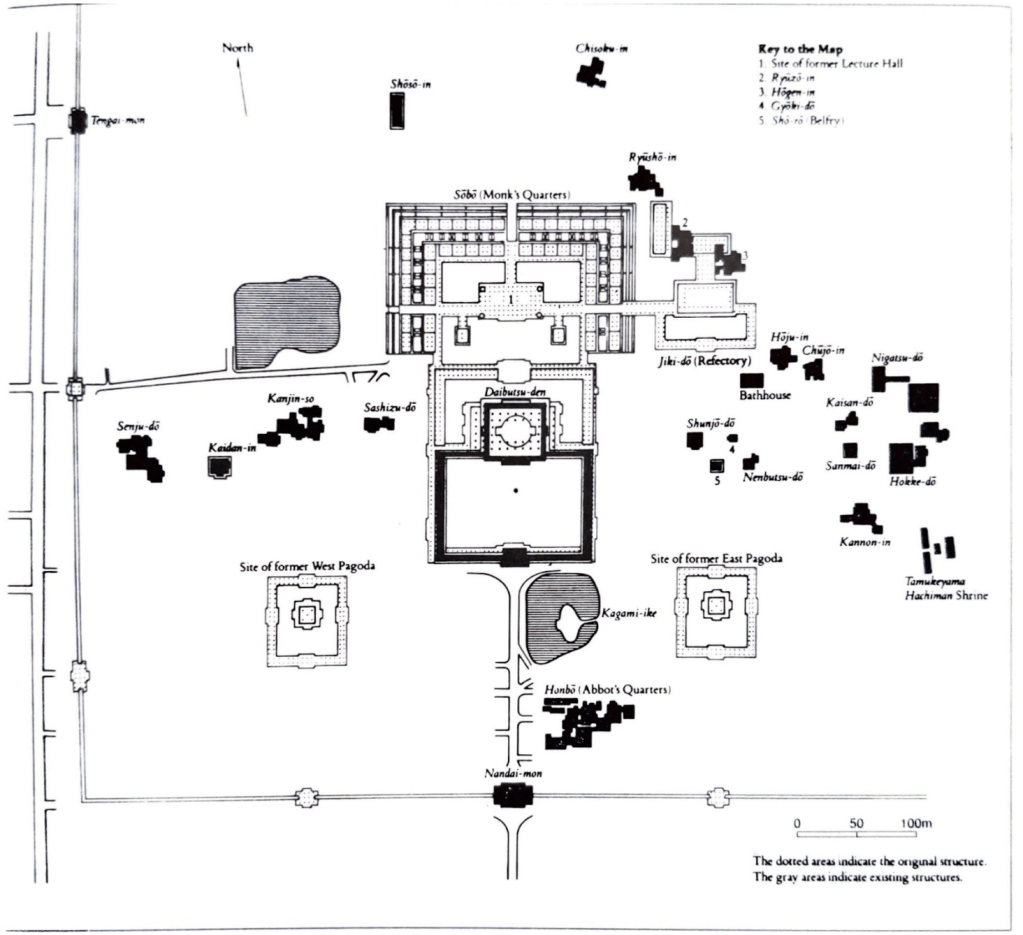

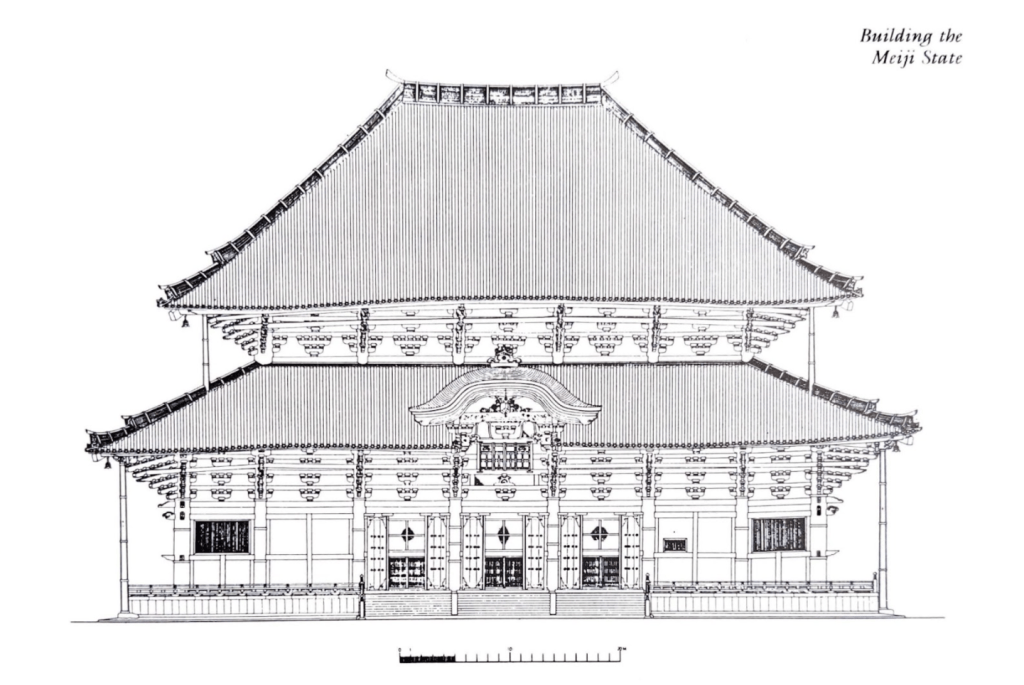

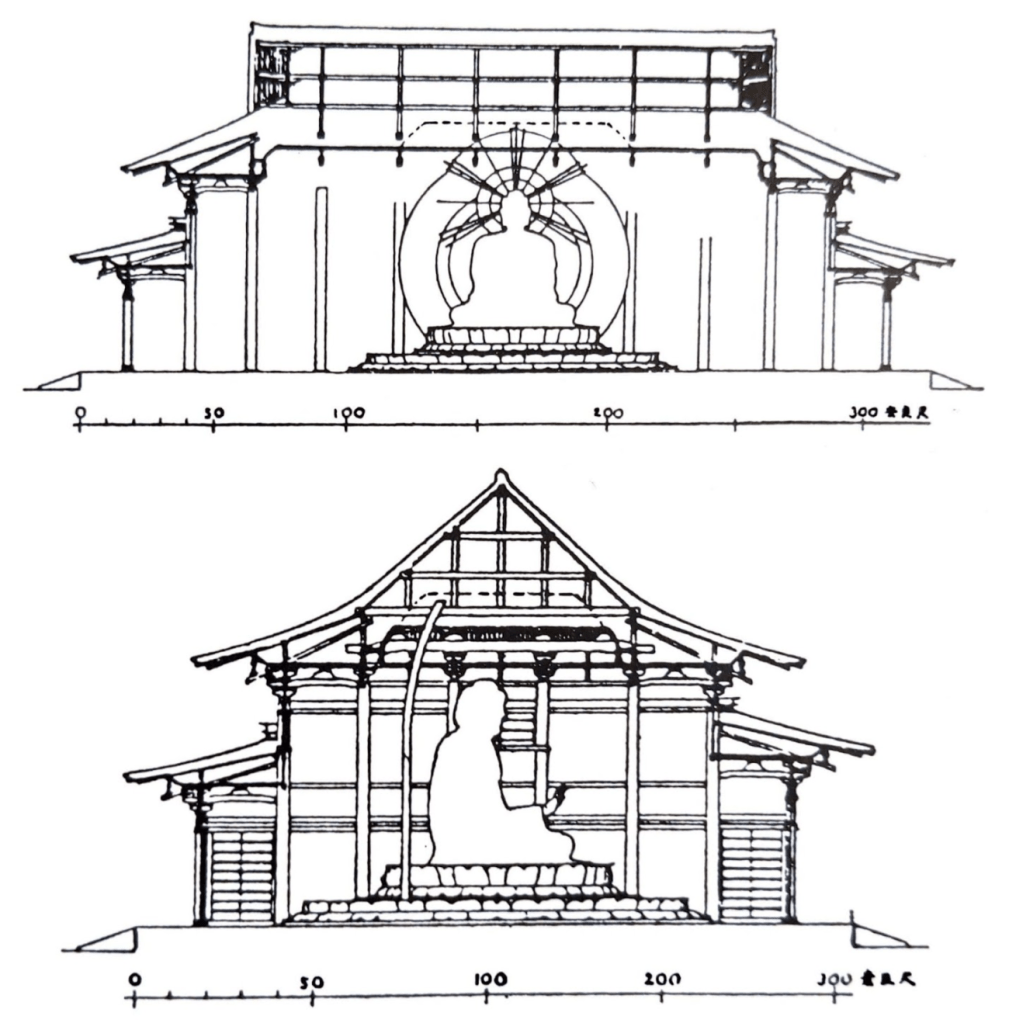

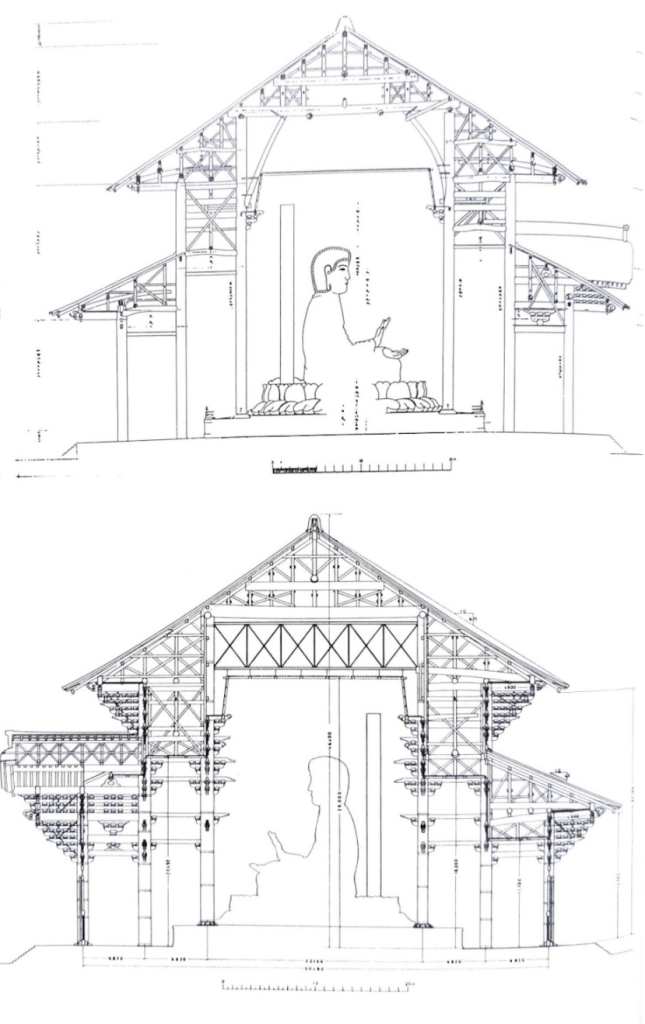

Although the temple has undergone multiple cycles of destruction and rebuilding due to fires, there has been research done which has resulted in a decent understanding of the original temple complex, and many of the rebuilt buildings are built to evoke the characteristics and grand scale of the original buildings. [1] The construction of the original temple complex was announced by Emperor Shomu in 743, [2] and the opening ceremony was held in 752. [3] The layout of the Todaiji complex, including both the existing buildings and some of the formerly existing ones, can be seen in Figure 1. A strong axial planning can be seen, with the southern gate, Nandaimon, allowing an entrance to a major avenue which leads to the Daibutsuden (elevation in Figures 2a and 2b), which encloses the Great Buddha statue. [4] The Buddha is massive compared to the structure, and by looking at the sections (Figures 3 and 4), it is understandable that the Buddha was cast before the structure was built around it. [5] There is a roofed corridor that encloses the space to the south of the Daibutsuden, with an entrance in the center of the southern portion of that corridor, on axis with the main avenue leading to the Daibutsuden and ultimately the Buddha statue itself. In earlier Buddhist temple designs, the corridor surrounded both the hall housing the Buddha as well as pagodas, all placed on the same axis, but by the time of construction of Todaiji, as visible in the site plan (Figure 1), the pagodas were moved outside of the corridor and to the east and west sides of the main avenue. [6] This arrangement was a new innovation in Japan, as it is not found in Korea or China, and had the effect of lowering the importance of pagodas and putting a stronger emphasis on the Buddha image. [7]

The pagodas, in addition to other structures of the complex such as the monks’ quarters, do not exist today, and as mentioned, most of the existing buildings are reconstructions. However, the Tengai-mon gate, Shoso-in, Tamukeyama shrine (labelled in Figure 1), and three log storehouses are from the original time period of construction in the Tempyo period (711-781). [8]

Historical Context

To understand the significance of Todaiji, it is important to look at the historical background of its construction. At the time of its construction, Buddhism had only been in Japan for a few centuries. It was originally introduced to Japan in the 6th century from the Paekche Kingdom in Korea. [9] This was done as a political move by the king of Paekche in hopes of being able to establish a military alliance. [10] There was some tension among conservatives in Japan regarding the introduction of the new religion, but by the time of Todaiji’s construction, Buddhism had become more accepted. [11]

Todaiji was built to serve as the headquarters of the kokubunji system, whereby Japan was divided into provinces, each with its own monastery and nunnery. [12] As the headquarters, it was also intended to be the architectural model of construction for the regional religious buildings as well. [13] It was designed with standardized measurements and simplicity so that its construction could easily be replicated in the provincial temples. [14]

Politically, this was also a significant project, as it served as an establishment of Buddhism as an official state religion under the rule of Emperor Shomu. [15] William A. Coaldrake writes that the temple was anatomically analogous to the Nara Palace―while the temple had the Great Buddha Hall (Daibutsuden) in its center, the palace had the Great Audience Hall (Daigokuden) at its center. [16] The temple was also enclosed by walls on the south and west, with three gates, in the same way that the palace was enclosed. [17] Thus, symbolically, the temple was conceived to represent the status of Buddhism as an official religion for the empire. The symmetrical arrangements of both the palace and the temple were based on planning in the Tang dynasty, with the intention of engineering a society “focused on a virtuous emperor reigning with the mandate of heaven”. [18]

As it will be explained in further detail later on, the temple complex is basically laid out with the Buddha statue being the most prized object of focus. Getting a deeper understanding of why this specific statue was significant to Emperor Shomu in a political context brings further clarity to its significance. The specific deity that is sculpted into the statue is the Vairocana Buddha, which is the focal deity of the Kegon sect of Buddhism. [19] This sect was based on the Flower Garland Sutra, which was translated into Chinese by request of Empress Wu. [20] It becomes clear why Emperor Shomu found this sect to be politically compatible, especially when considering the background of Empress Wu’s motivation to have the sutra translated:

Its textual complexity and convenient ambiguity gave Shōmu ample scope to construe its spiritual message of a centralising spiritual force in the universe into an expedient religious justification for tightening imperial authority.This was based on the precedent furnished by Empress Wu herself. In order to strengthen her authority she sponsored Buddhism in general and the Huayan (Kegon) sect in particular. Buddhism with its equitable view of women rulers, and the Huayan sutra with its principal notion of a centralizing deity, provided powerful religious underpinnings for her position in the Tang court, dominated as it was by male-oriented Confucian and Daoist ideology. [21]

As it was the Flower Garland Sutra that allowed Wu to assert the legitimacy of her power, it is understandable that Shomu would see the religious sect based on this sutra as attractive politically. Empress Wu herself had sponsored the construction of Buddhist images, with the most impressive being a 13.37 meter tall carving of the Vairocana Buddha. [22] Similarly, in the Silla Kingdom in Korea, the Flower Garland Sutra was also used as a justification for a Buddhist state-building. [23] This sponsorship of construction of Buddhist images as part of a statement of political power was emulated by Shomu.

The sutra is believed by the Mahayana tradition to be the first sermon by the Buddha following his enlightenment, and has been described as “being abstruse and almost impossible to comprehend.” [24] Because of this, the Buddha preached simpler sermons following this one. An excerpt of a translation of this sutra illustrates the type of language used:

This is the place where all the Buddhas live peacefully. This is the dwelling place where a single eon permeates all eons and all eons permeate one eon without loss of any of their own characteristics … This is the dwelling place where one sentient being permeates all sentient beings and all sentient beings permeate one sentient being without loss of any of their own characteristics. [25]

The level of ambiguity, lack of clarity, and almost contradictory or paradoxical language is apparent. Although there is this level of ambiguity, it is clear that it is referring to an idealized place of spiritual communion. Within the view of the Kegon sect, an establishment of a Buddhist state would seek to establish this type of communion. [26] However, because the sutra is written in ambiguous language, it “left room for the persistence of strong indigenous customs, thus enabling egalitarian spirituality to coexist with political and social hierarchy.” [27]

The significance of the building project can be understood by studying the impressive construction process and procurement of materials. The 48 principal pillars, used in the Daibutsuden, each 30 meters in length, were sourced from Harima, over 80 kilometers away. Other timbers were sourced around Lake Biwa, 40 kilometers away, and rivers were used to float down the timbers. There was extensive manpower involved in this stage, “employing 227 site supervisors, 917 master builders and 1,483 labourers.” The project also involved extensive excavation, with the Western portion of Mount Wakakusa being excavated up to 30 meters deep. [28]

The casting of the Great Buddha was a significant endeavor for its time, as it is now believed to be the “the largest bronze casting undertaken in the ancient world,” and it was done with up to seven smelting furnaces. Emperor Shomu “may have declared in 743 that he wished to make the ‘utmost use of the nation’s resources of metal in the casting of this image’.” It just so happened that gold had just been discovered in Mutsu province, over 400 kilometers away, and this allowed for the gilding of the Buddha. [29]

This immense system of labor and resources which extended over a large geographical portion of Japan demonstrated the significance of the Todaiji project to Shomu in establishing his authority as the leader of a Buddhist state. Emperor Shomu’s own words upon the discovery of the gold demonstrate the extent to which he was seeking to establish a new political order which was officially Buddhist:

This is the Word of the Sovereign who is the Servant of the Three Treasures, that he humbly speaks before the Image of Lochana.

“In this land of Yamato since the beginning … Gold … was thought not to exist. But in the East of the land which we rule … Gold has been found.

Hearing this We were astonished and rejoiced, and feeling that this is a Gift bestowed upon Us by the love and blessing of Lochana Buddha, We have received it with reverence and humbly accepted it, and have brought with Us all Our officials to worship and give thanks.” [30]

The use of the term “Servant of the Three Treasures” and the humility by which Shomu expresses his appreciation for the discovery of gold, which he is attributing to the Buddha, is significant in that it demonstrates his submission to Buddhism; this type of humility signified a fundamental change in the role of the emperor within the context of a Buddhist state. [31]

Tanizaki’s View

The essay In Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanizaki contrasts Japanese aesthetics in traditional arts with the Western ideals of aesthetics. Overall, it claims that Japanese aesthetics favor a more subdued treatment of light, and that this type of gentle lighting is ideal when used harmoniously with appropriately designed material culture.

One example of this appreciation for a subdued lighting interacting with objects can be found in Tanizaki’s description of traditional Japanese lacquerware. Tanizaki describes a traditional Japanese restaurant, the Waranjiya, which he was fond of. To his disappointment, upon one visit he learned that the candlelight which he had been used to experiencing at the restaurant had been replaced with electric lighting, and as a result he requested a candlestand be brought to his table. [32] This allowed him to experience the beauty of the lacquerware in the way he describes it was meant to be appreciated:

And I realized then that only in dim half-light is the true beauty of Japanese laqcuerware revealed. The rooms at the Waranjiya are about nine feet square, the size of a comfortable little tearoom, and the alcove pillars and ceilings glow with a faint smoky luster, dark even in the light of the lamp. But in the still dimmer light of the candlestand, as I gazed at the trays and bowls standing in the shadows cast by that flickering point of flame, I discovered in the gloss of this lacquerware a depth and richness like that of a still, dark pond, a beauty I had not before seen. [33]

It was not just the specific qualities of the lacquerware itself, but rather the way that the subdued lighting interacted with it which gave the ultimate aesthetic experience. Tanizaki explains that the traditional colors of lacquerware were dark colors, such as “black, brown, or red, colors built up of countless layers of darkness.” [34]

Furthermore, this experience of subdued lighting on dark lacquerware allows for carefully and modestly applied gold or silver to be well appreciated. For specks of gold or silver applied to the lacquerware, Tanizaki writes that their presence on a dark background and low lighting will allow those patterns to “turn somber, refined, dignified.” [35] He continues to describe the behavior of gold as “[gleaming] forth from out of the darkness and [reflecting] the lamplight.” [36]

This understanding of aesthetics clarifies the attitude by which Todaiji and its treatment of the Great Buddha statue may have been conceived. The Buddha is described as follows: “Inside the hall stood the statue of Vairocana, symbolic core of the monastery, soaring high in the darkened, incense-laden space. The colossal gilt-bronze image, framed by the geometry of great timber pillars and beams, shimmered in the light of flickering candles.” [37] It is evident that the space was intended to be dark, and that the bronze of the statue was to be appreciated within that darkness and low lighting of the candles. There is a sense of modesty of lighting and material that is able to bring the visual focus of attention to the Buddha in the same way that the low lighting of the candles allowed for the appreciation of the lacquerware.

Tanizaki’s description of Japanese architectural tradition also shows a focus on forming shadows in the spaces formed. He begins by contrasting the construction of Japanese temples to the construction of Gothic cathedrals; while the Gothic cathedrals are about thrusting up the roofs into the heavens, the Japanese temples are defined by heavy roofs which result in “a heavy darkness that hangs beneath the eaves”. [38] Tanizaki even describes this darkness as “cavernous”. [39] He describes the construction of Japanese buildings as beginning with the construction of a parasol, under which the rest of the rooms are laid out. [40] In the same way the Gothic cathedrals are fundamentally different from Japanese temples, the roofs also are expressed differently, with the Japanese roofs having long overhanging eaves, casting deep shadows, which contrasts from the Western roofs, which Tanizaki argues are more for keeping out wind and moisture than they are about keeping out the sunlight. [41]

This establishment of a shadow being so dominant in the construction of a traditional building naturally impacts the experience of rooms in the building. While the Gothic cathedrals are known for their ability to maximize the amount of light that penetrates into the building due to their structure, the long eaves of the Japanese temple ensure that there is little to no direct light in any of the rooms. It is for this reason that Tanizaki argues that “the beauty of a Japanese room depends on a variation of shadows, heavy shadows against light shadows.” [42]

It is within these rooms of shadows that attention can be called to certain elements within a room. As he did with the lacquerware, Tanizaki also focuses on the effect of gold within a dimly-lit room, such as that found on a sliding door or screen: “How, in such a dark place, gold draws so much light to itself is a mystery to me. But I see why in ancient times statues of the Buddha were gilt with gold and why gold leaf covered the walls of the homes of the nobility. Modern man, in his well-lit house, knows nothing of the beauty of gold.” [43]

Because the roof in traditional Japanese architecture is so heavy, compared to what is below it—a post-and-lintel system of timber—there is an ability for the building to produce the variation of shadows within itself, and this variation of shadows can continue deep into the building, through multiple structural bays. The lack of the need of load-bearing walls is part of what allows for the relative sense of lightness below the roof. Furthermore, the interior bays of many Japanese spaces are partitioned by shoji screens, which are also materially light and therefore allow for a continuation of the dim lighting’s penetration between bays.

Tanizaki expresses his appreciation for the daylight that makes its way through the various layers of the house, eventually landing on a shoji screen: “The little sunlight from the garden that manages to make its way beneath the eaves and through the corridors has by then lost its power to illuminate, seems drained of the complexion of life. It can do no more than accentuate the whiteness of the paper.” [44] Tanizaki describes the shoji as having a “pale white glow”. [45]

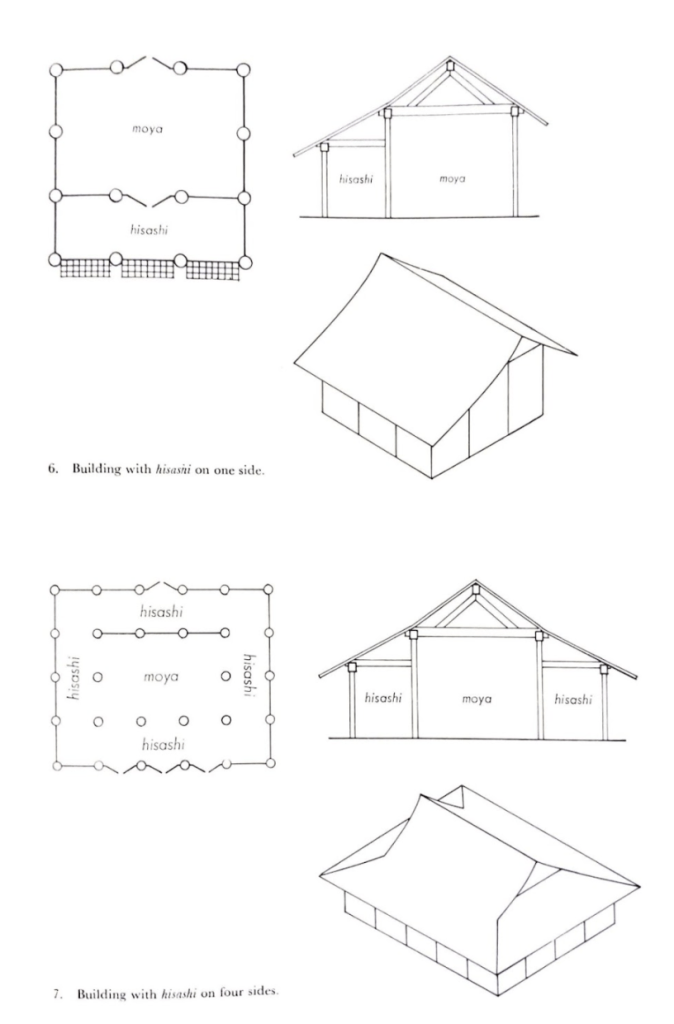

There is therefore a complexity in lighting that is made possible due to the structural and architectural character of traditional Japanese architecture. Figure 5 shows some typological patterns of Japanese timber structures. There are multiple variations, but in all of the examples shown, there is an innermost bay called the moya which is surrounded by outer spaces. It is therefore predictable that when indirect daylight enters the building—already blocked from most direct daylight by its massive roofs— it will move into the building, and the deepest, innermost bays will have the lowest levels of daylighting.

Because it has been about ten years since my visit to Todaiji, I have only faint memories of the experience. However, I do remember that upon entering, it was not the Buddha statue that I first noticed, even though it is the largest statue in the entire hall and the focal object of the hall. To be fair, it was probably because I was not entering the temple from the central doorway on axis with the main avenue because I was using the path designed to control visitor traffic. I am sure I would have noticed it at first had I entered through the central entrance. However, the point is that because the Buddha statue is placed in the very center of the hall, as visible in the sections of Figures 3 and 4, the lighting is lower in that part of the hall. Figure 6 shows the subdued lighting in the center of the Daibutsuden, which serves to draw one’s attention to the luster of metallic materials in and surrounding the statue.

This treatment of the most prized treasure in the entire temple complex is definitely different from what would be expected in Western sacred architecture, and is a good example of Tanizaki’s argument that beauty must be experienced within a subdued lighting. He describes the experience of being in a Japanese temple:

And surely you have seen, in the darkness of the innermost rooms of these huge buildings, to which sunlight never penetrates, how the gold leaf of a sliding door or screen will pick up a distant glimmer from the garden, then suddenly send forth an ethereal glow … In no other setting is gold quite so exquisitely beautiful … But I see why in ancient times statues of the Buddha were gilt with gold. [46]

Although Japanese aesthetics are somewhat difficult to generalize due to its historically diverse set of both local and foreign cultural influences, there are some prevalent aesthetic patterns that emerge in Japanese tradition. There is an appreciation for the beauty found in austerity. A passage by the Buddhist monk Kenko (1283-1350) expresses this sentiment:

Are we to look at cherry blossoms only in full bloom, the moon only when it is cloudless? To long for the moon while looking on the rain, to lower the blinds and be unaware of the passing of the spring—these are even more deeply moving. Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with faded flowers are worthier of our admiration. [47]

Japan is well-known for its appreciation of nature, and while there is particular appreciation for the time of cherry blossoms blooming in spring, and the leaves turning color in the autumn, a further level of appreciation of nature allows for the appreciation of nature as-is, even in its mundane moments. When observing the behavior of light inside of Todaiji, this appreciation for the austere can be found in the treatment of light. The light is able to behave and be experienced authentically within the interior volume of the temple.

Conclusion

While it has been a while since I visited Todaiji, learning about it from a historical perspective has given me a new view and appreciation for it. The temple treasures its most sacred object, the Buddha statue, by placing it deep inside the very center of a hall in the center of the temple complex. Very little light reaches that central part of the Buddha Hall, but with the assistance of some candle lighting, it is just enough to allow the bronze of the statue to be appreciated. This is the kind of experience of shadows that Tanizaki is nostalgic for. In the end of his book, Tanizaki expresses his dissatisfaction with the modernization of electricity, which he describes as Japan being “too anxious to imitate America in every way it can.” [48] He has accepted this change as something that is inevitable and cannot be stopped, but hopes that his writing would help save “this world of shadows we are losing.” [49]

This struggle of Japan having to reconcile their external influences with what is characteristically or authentically Japanese is something that is not unique to Tanizaki’s grievances. It is a common theme in Japanese culture, including in architecture, which the architect Arata Isozaki describes as the “Japan-ness problematic.” [50] He explains that while the architect Chuta Ito saw Japanese architecture as necessarily being “ ‘an original product of the Japanese people,’ ” Sutemi Horiguchi believed that Japanese architecture is defined by the “Japanization of foreign imports,” known as wayo-ka. [51] To Horiguchi, the Ise Shrine was considered a “foremost example of Japanese architecture” [52] despite the fact that its specific typology was inherited by religious influence from the Asian continent, and there were other shrines which had a typology more original to Japan. [53] Even though the architectural style of Ise was foreign, its ability to harmonize with its environment was viewed by Horiguchi as uniquely Japanese. [54] Due to Japan’s historical interactions with neighboring cultures, it is reasonable to assume that much of the architecture and aesthetic style that Tanizaki argues is being lost is also not original to Japan but rather an import that has been Japanized. Afterall, the project of Todaiji was largely influenced by China, and the temple is associated with a religion not original to Japan. Perhaps this view means that despite the modernization and introduction of electric light that Tanizaki viewed as a threat, Japan would still find a way to take these imports and make them uniquely Japanese. As mentioned, there was initial opposition to the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, but eventually it was adapted to Japanese culture, and resulted in an evolution of the Japanese aesthetic as opposed to a threat to the aesthetic. Perhaps the moment that Tanizaki found himself in was not a moment of the Japanese style being taken over by the Western style, but rather the beginning of a new evolution in the Japanese aesthetic.

References

- Kakichi Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, trans. May N. Parent and Nancy S. Steinhardt (Tokyo: New York: Kodansha International ; Distributed through Harper & Row, 1980), 111.

- William H. Coaldrake, “Great Halls of Religion and State,” in Architecture and Authority in Japan (New York, NY: Routledge), 77.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 78.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 71-72.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 78.

- Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, 18.

- Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, 18.

- Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, 13, 111.

- Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, 14.

- Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition: From Earliest times to 1600, Vol. 1 (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1958), 552.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 111.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 70.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 71.

- Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan, 124.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 71.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 71.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 73.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 54.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 75.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 76.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 76.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 76.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 108.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 108.

- Translated in De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 109.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 109.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 109.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 77.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 78.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 105.

- De Bary, Keene, Tanabe, and Varley, Sources of Japanese Tradition, 105-106.

- Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, trans. Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker (Bramford, CT: Leete’s Island Books, 2017), accessed March 2, 2021, ProQuest Ebook Central, 13.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 13.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 13.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 13-14.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 14.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 74.

- Coaldrake, “Great Halls,” 74.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 17.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 17.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 17.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 18.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 22.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 21.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 21.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 22.

- Donald Keene, “Japanese Aesthetics,” Philosophy East and West 19, no. 3 (1969): 293-306, accessed April 12, 2021. doi:10.2307/1397586, 298.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 35.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 35.

- Arata Isozaki and David B. Stewart, Japan-ness in Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006), 123.

- Isozaki and Stewart, Japan-ness in Architecture, 123.

- Isozaki and Stewart, Japan-ness in Architecture, 123.

- Isozaki and Stewart, Japan-ness in Architecture, 119.

- Isozaki and Stewart, Japan-ness in Architecture, 123-4.

Bibliography

Cleary, Thomas F. The Flower Ornament Scripture: a Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Boston: Shambhala, 1993.

Coaldrake, William H. “Great Halls of Religion and State.” In Architecture and Authority in Japan, 52-80. New York, NY: Routledge, 1996.

De Bary, Theodore, Keene, Donald, Tanabe, George, and Paul Varley. Sources of Japanese Tradition: From Earliest times to 1600. Vol. 1. New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1958.

Isozaki, Arata, and David B. Stewart. Japan-ness in Architecture. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006.

Keene, Donald. “Japanese Aesthetics.” Philosophy East and West 19, no. 3 (1969): 293-306. Accessed April 12, 2021. doi:10.2307/1397586.

Suzuki, Kakichi. Early Buddhist Architecture in Japan. Translated by Mary N. Parent and Nancy S. Steinhardt. 1st ed. Japanese Arts Library 9. Tokyo : New York: Kodansha International ; Distributed through Harper & Row, 1980.

Tanizaki, Junichiro. In Praise of Shadows. Translated by Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker. Bramford, CT: Leete’s Island Books, 2017. Accessed March 2, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Weinstein, Stanley. Buddhism under the T’ang. London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press, 1987, p. 45.